Citizenship, Race, and Place: Frontiers in Asian American History

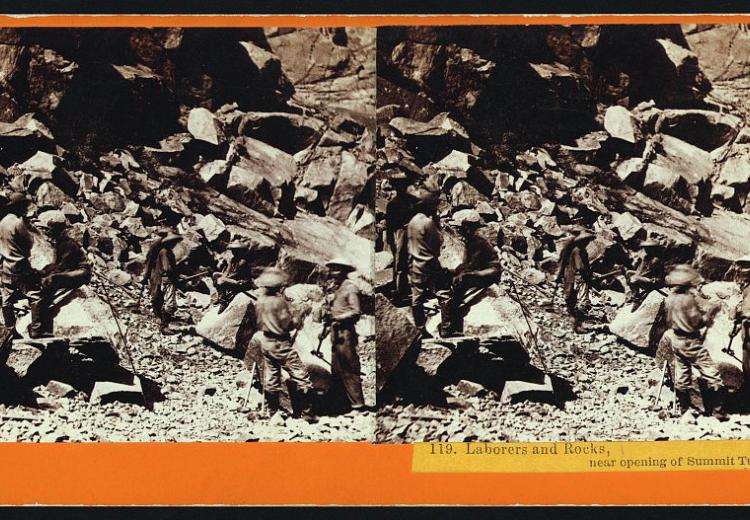

Chinese laborers and rocks near opening of Summit Tunnel

Courtesy Library of Congress

The idea of a “frontier” has existed since before our nation’s founding. Frontiers as physical spaces have long been in continuous motion. Frontiers can be imagined spaces that changed due to war, displacement, migration, settlement, or treaties. The words used to describe this movement vary depending on one’s perspective: progress, tragedy, opportunity, isolation.

This year’s National History Day® (NHD) theme, Frontiers in History: People, Places, Ideas, invites students to investigate how those interactions shaped frontiers as places and ideas. This article is framed by the compelling question, “How have Asian Americans traversed and transcended frontiers in history?” It considers how Asian Americans experienced frontiers as builders, resisters, and activists.

We begin with the role of Chinese immigrants in completing one of the most significant infrastructure projects of the nineteenth century, the transcontinental railroad. Their participation shaped the boundaries of the American West and whom the U.S. government considered American. Questions about citizenship and belonging echoed into the twentieth century with the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Incarcerees experienced the frontier in familiar ways–the colliding of cultures, the need to innovate in the face of unimaginable obstacles–and also in ways that were unique to their wartime imprisonment. These stories allow us to center the experiences of Asian Americans in understanding the history of the frontier. We will consider the power of the frontier as a physical place and, more broadly, why place matters.

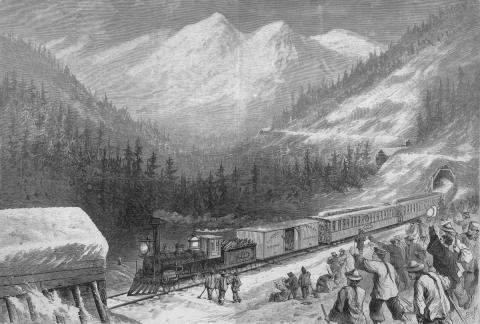

Builders on the Frontier: The Transcontinental Railroad

The 1848 California Gold Rush brought the first Chinese migrants to the western United States. Many found opportunities in the mining industry, others on farms or running small businesses. The construction of a rail line across the U.S. in the mid-1860s required a massive workforce, a demand both the Union Pacific and the Central Pacific Railways struggled to meet. Despite racial prejudice, both companies began actively recruiting Chinese workers, who could be paid as little as half to two-thirds the wage offered to native-born U.S. workers for the same backbreaking work.

Records are inexact, so the precise number of Chinese workers is unclear. They built nearly 690 miles of railroad between 1864 and 1869. At any one time, 10,000 to 15,000 Chinese worked on the construction. Responsible for building sections of the track through the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, Chinese laborers conquered rock, granite, and conifer forests. They encountered life-threatening weather, including blizzards and avalanches. The most challenging conditions were found near the summit of Donner Pass. At an elevation of 7,200 feet, workers struggled to breathe while laying track.1 They built several tunnels through solid granite using black powder and dangerous chemicals. As master masons, these Chinese laborers also built a 75-foot retaining wall at Donner Pass between the two tunnels—by hand, without using any mortar—to support the roadbed. It became known as China Wall, a remarkable engineering feat. In 2021, the National Trust for Historic Preservation designated this section of the railway among the most endangered historic places. The labor of Chinese immigrants was essential to the Transcontinental Railroad, the critical infrastructure that supported the nineteenth-century expansion of the American frontier. On May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit, Utah, the golden spike connected the Central Pacific track from Sacramento, California, with the Union Pacific track from Omaha, Nebraska. While many of their efforts have been unrecognized or forgotten, Chinese laborers transformed the landscape and development of the United States.

Resisters on the Frontier: Confronting Nativism, Racism, and Exclusion

As Chinese laborers found employment and established a foothold in this American frontier, they encountered virulent racism and violence from their white neighbors. Rather than viewing Chinese workers as equals, white workers viewed them as “coolies” (unskilled laborers) or “virtual semi-slaves,” who collaborated with corporations to bring down wages and push out the white working class.2 White workers and their families boycotted and threatened companies that relied on Chinese workers. In the words of historian Erika Lee, anti-Chinese politicians and white residents sought to “[sustain] the West as a ‘white man’s frontier.’”3 Nativists expressed anti-Chinese prejudice through violence. These vigilante actions rarely resulted in prosecution and, in some cases, received the support of local law enforcement.

Nativists successfully pressured legislators to set xenophobic or prejudiced attitudes into law. The Burlingame-Seward Treaty (1868) between the United States and China formally committed the U.S. to protect Chinese immigrants’ rights, including the right to move freely and trade. The treaty signaled an opportunity for a more positive relationship, but it clashed with the interests of western nativists.4 In reaction, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Foran Act of 1885 to redefine the country’s obligations. These laws blocked Chinese immigration and barred immigrants from becoming U.S. citizens.5 However, federal legislation did not end the debate nor quell white discontent. Instead, it exacerbated anti-Chinese sentiment and increased violence. The federal government could not enforce immigration restrictions, and budgetary limits meant that any effort at mass deportation was impractical. To nativists on the west coast, the federal government’s ineffective enforcement served as proof that Chinese immigrants and corporations were conspiring to mock the will of the people.6

Even under consistent threat, many Chinese migrants vocally opposed the passage of xenophobic laws and built support networks. These networks included family and friends, immigration lawyers, and sympathetic whites.7 Chinese Americans challenged state and local legislation in state and federal courts.8 When federal laws passed, they continued their fights in federal courts. Hoping for a sympathetic response to the mistreatment of Chinese migrants, many wrote letters to Presidents Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and Woodrow Wilson.9 While the process of exclusion did not end immediately, it raised the question of who could be an American.

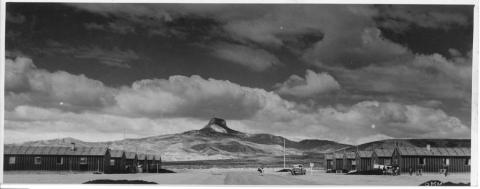

Activists on the Frontier: Japanese Incarceration Camps

After the 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor, the federal government characterized the Japanese and Japanese American populations as dangerous enemies. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the evacuation of people with Japanese ancestry from the West Coast to military zones in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming. Imposing watch towers, rows of barracks, and barbed wire fences separated Japanese citizens and Japanese Americans from seemingly desolate landscapes. More than 127,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were imprisoned until 1945. By removing Japanese Americans from their homes and relocating this racial group to remote locations, the United States government created new frontiers beyond the boundaries of white American communities in the twentieth century on the settled land of Native Nations.

While interactions on frontiers can bring about the exchange of goods and ideas, boundaries can also separate people, places, or ideas. Incarceration camps insinuated that the Issei and Nisei (first- and second-generation Japanese Americans) were guilty of espionage on behalf of the Japanese Empire. The War Relocation Authority (WRA) devised a questionnaire administered to adults in the camps to determine their allegiance and assess their loyalty to the United States. The final two questions caused the most confusion. Question 27 asked Nisei men, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?”

As a follow-up, Question 28 asked if they would swear allegiance to the United States and forsake any loyalty to the Emperor of Japan. As American citizens recently stripped of their civil rights, many responded to these questions: no, no. For some, these were simply honest answers to the questions asked. Others considered the courage to answer honestly a form of activism. Labeled as “disloyal,” these activists, who became known as “no-no boys” for their peaceful act of protest, were moved to Tule Lake, an incarceration camp in California.

Another act of resistance can be seen with Kiyoshi Okamoto’s formation of the “Fair Play Committee of One” at Heart Mountain in Wyoming in response to the WRA questionnaire in 1943. In an oral history, Sam Mihara, a former Heart Mountain incarceree who was imprisoned at age nine, recalled Okamoto organizing others at the camp. He noted:

I remember a gathering after dinner of these people having a meeting and loud voices. And how people like Okamoto and others would describe the conditions and their philosophy that we should not serve until our rights were restored. And that kept building up until there were some eighty-five Japanese Americans in the camp at Heart Mountain, who took the active step that when the draft came in, they decided not to go and board buses to go to a physical examination, which is the first step in the draft process.

In his oral history on EDSITEment, Mihara described his school in the camp, his childhood friends, and where their imaginations could take them outside of the barracks. While a fence separated them from other communities in Wyoming, the young schoolboys often slipped through the fence, finding rattlesnakes and arrowheads on the other side. Activism that began decades prior in the camps continued into the post-war years. The American government acknowledged their fault in 1988 with reparations to Japanese Americans after their successful campaign for a formal apology and compensation for all they had lost in the three years behind barbed-wire fences. Today, we continue to confront the legacies of Japanese incarceration and the multiple meanings of “frontiers.”

Conclusion

As the United States expanded its borders abroad and at home, the frontier never quite closed. Frontiers continued to morph into tools that justified U.S. power by constructing and reinforcing racial differences. The frontier’s physical and conceptual evolution contributed to debates over land rights, access, and Americanness. Asian Americans contested the consequences of frontiers in multiple places—the courtroom, schools, their homes—in ways that showed the limitations of “the frontier” when held accountable to the U.S. promise of equality. When we look to the experiences of Chinese, American Indian, Japanese Americans, white, Black, and Mexican Americans, across time and space, we see how much the history of the United States challenges and redefines frontiers. Pondering “why here?” pushes us to ask new questions about people, places, and ideas in the interest of telling a fuller, more inclusive history of the United States.

-

Gordon H. Chang, Ghosts of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019), 75.

-

Richard White, The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 520.

-

Erika Lee, America for Americans: A History of Xenophobia in the United States (New York: Basic Books, 2019), 78.

-

Chang, Ghosts of Gold Mountain, 218–219.

-

Chang, Ghosts of Gold Mountain, 231–232.

-

Richard White, Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2011), 305.

-

Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882-1943 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 104, 130.

-

Roger Daniels, Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882 (New York: Hill and Wang, 2004), 20.

-

Lee, At America’s Gates, 114.