Jack London’s “To Build A Fire”

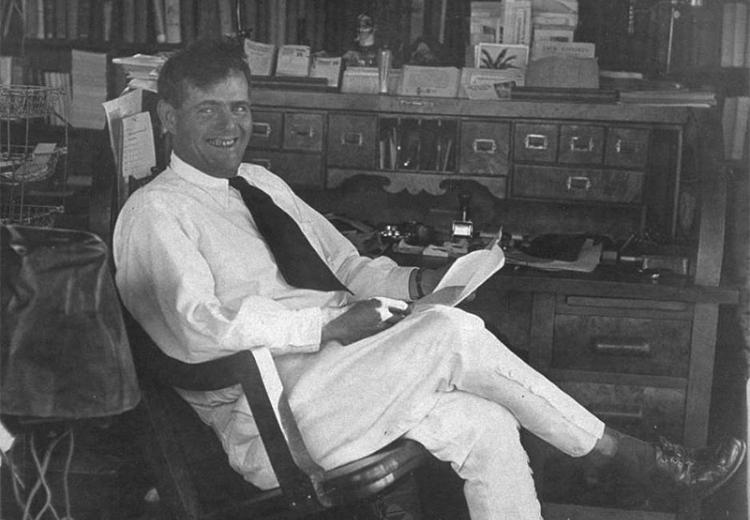

Jack London in his office, 1916.

Thinking about the Story | The Man's Motives and Purpose | Assessing the Man | Thinking with the Story | American Acquisitiveness and Enterprise | Science, Technology, and the Mastery of Nature | About the images | Freedom and Individuality: "To Build a Fire" by Jack London from What So Proudly We Hail on Vimeo.

Directions

This Launchpad, adapted from What So Proudly We Hail provides background materials and discussion questions to enhance your understanding and stimulate conversation about “To Build A Fire.” After learning about the author, Jack London, read his story. After discussing or thinking about the questions, click on the videos to hear editors Amy A. Kass and Leon R. Kass converse with guest host William Schambra (Hudson Institute) about the story. These videos are meant to raise additional questions and enhance discussion, not replace it.

Introduction

Jack London, like the unnamed man in this story, lived on the edge. Born in 1876, he died a short forty years later. As a young man, he was a full-fledged participant in the Yukon Gold Rush of 1897. Like many others at the time, London made the incredibly arduous journey by foot and handcrafted boat from Dyea in Alaska over Chilkoot Pass—a three-quarter-mile, 45-degree-angled obstacle course—and eventually down the Yukon River into the Northwest Territories. The only gold he brought back, however, was an experience that he would mine for gems of literature for much of his writing life, as evidenced in his well-known novels like Call of the Wild and White Fang, as well as in “To Build a Fire” (1908), all of which draw on the places he saw and the people he met during those hope-filled and brutal times in the Northwestern Yukon Territories.

Read “To Build a Fire”

Thinking about the Story

Citizens from many nations, for quite different reasons, sought to penetrate the Northwest Territories. We can imagine, for example, a story like London’s about a French Jesuit priest losing his life while trudging through the Northern winter for the purpose of baptizing a newborn Huron Indian. We would be invited by such a tale to admire or even be inspired by the deep piety, the sacrificial spirituality, of such a Frenchman.

We also have an historical British example in Sir John Franklin, who set out in 1845 with 129 men and two amply stocked ships to find the Northwest Passage, a route through the Arctic from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Although his expedition failed and all aboard were lost, Franklin stood for many decades as a proud symbol of British naval prowess and national, even imperial, honor. Noble impulses, like piety and honor, still inspire.

But Jack London’s anonymous adventurer is out on the Yukon River, all alone in the dead of winter, searching about for a profitable business opportunity: Jack London’s man is clearly an American. So are the story’s larger themes.

But before getting to these themes, we need to look carefully at the protagonist of the story: his character, his deeds, and his purposes. We will also want to decide what we think of him.

The Man

- Characterize the man, drawing on the descriptions of his attitudes, manner, and deeds

- Compare the man and the dog. How do they differ?

- The man knows how “to build a fire.” What does this tell us about him?

- The narrator says: “The trouble with him was that he was without imagination. He was quick and alert in the things of life, but only in the things, and not in the significances” What does this mean? Is it a problem?

- What is the significance of the fact that the man is not named? Is the man responsible for what happens to him? Or is he just an unlucky victim of accident (“It happened”)?

Watch: Is the Man Typically American?

Watch: Why is the Man Nameless?

The Man’s Motives and Purposes

- What moves the man to act as he does?

- Trace his changing attitude toward the old-timer from Sulphur Creek. Why does he resist the old man’s advice? Why does he acknowledge, as he lies dying, that the old man was right?

- Given the opportunity to make this journey again, under similar circumstances, do you think he would take it? What did you learn from his experience?

Assessing the Man

- What do you think of the man?

- Do you regard him as an admirable hero—independent, resourceful, rugged, and resilient? Do you regard him as a reckless fool—proud, overconfident, unimaginative, and blind? As something in between? In some other way? Explain.

- Had he successfully made it back to camp, would your judgment of him differ? What do you think London thinks of his own protagonist?

- Is the man a tragic hero?

Watch: Is this story a tragedy?

Thinking with the Story

Americans have traditionally been known for, and generally proud of, their independence and self-reliance, their freedom and individualism, their enterprising and adventurous spirit, their courage and endurance in grappling with the forces of nature, their success through science and technology in making the world a more hospitable place for human life. These national traits of character, long celebrated in stories of exploration, adventure, the settling of the frontier, and the founding of industries are in fact encouraged by the American creed as it emerges and through our founding principles and documents.

So, for example, the Declaration of Independence conceives of human beings as free-standing, independent individuals, and it asserts that each of us has an inalienable right to pursue our own happiness, each according to his own lights. The United States Constitution established a large commercial republic, largely on the belief (defended in Federalist No. 10) that encouragement of material self-interest is far less threatening to stable and free government than is a politics dominated by zeal for high-minded opinion (be it religious, philosophical, or political) or a politics dominated by passionate attachment to charismatic leaders and ambitious men.

The Constitution also embraced the goal of progress in natural science and the useful arts, by calling for copyright and patent protection for authors and inventors. (Students and readers are encouraged to read these Founding Documents in order to better appreciate the questions that follow.)

London’s story invites reflection on these features of the American character, with an eye to identifying and assessing their strengths and their weaknesses.

American Individualism

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the “rugged individual”? Give some examples of the rugged individual in literature, in movies, or in your own life. What do we admire about these people? What do we find lacking in them?

- Could America have become what it is today without risk-takers like London’s protagonist? Or is there a difference between him and the risk-takers who tamed the wilderness and settled the frontier? If so, what is it?

- Do you think London’s character is peculiarly American? Could the no-named man be any man from anywhere?

Watch: Individualism and its limits

American Acquisitiveness and Enterprise

- How should we evaluate people who undertake dangerous enterprises with a desire for commercial gain?

- Should we be ashamed that we Americans are likely to be motivated more by material or commercial impulses than by other more exalted motives (e.g., religious piety, love of justice)? Why, or why not?

Watch: A man without imagination

Finally we must ask questions about the man’s relationship to nature in all its inhospitable harshness.

Science, Technology, and the Mastery of Nature

- Are there limits to our efforts to tame nature? If so, what are they?

- Does our reliance on science blind us to certain deeper truths about nature and our relation to it? (Consider, in this regard, the strengths and weaknesses of living in the world guided by—as in the story—watches and thermometers.)

- What is, and what should be, our attitude toward the natural world, especially if nature is indifferent to human beings and often hostile to our purposes? Who in the story is a better model, the man or the dog?

- What does the story teach us about death? The man realizes that he wants to “meet death with dignity” (as opposed to “running around like a chicken with its head cut off”). What do we mean when we talk of meeting death with dignity?

Watch: Mastering nature

Over the course of this year, EDSITEment will be showcasing a series of innovative lessons which use classic American short stories to teach civics. This lesson is adapted from http://www.whatsoproudlywehail.org/. Click here to see EDSITEment's feature on Leon and Amy Kass's innovative civics curriculum

About the Images

- Jack London photo (Introduction)

- Klondike gold miner (Thinking About the Story)

- Illustration from story To Build a Fire. First published in The Century Magazine, v.76, August, 1908 (Thinking With the Story)