Grassroots Perspectives on the Civil Rights Movement: Focus on Women

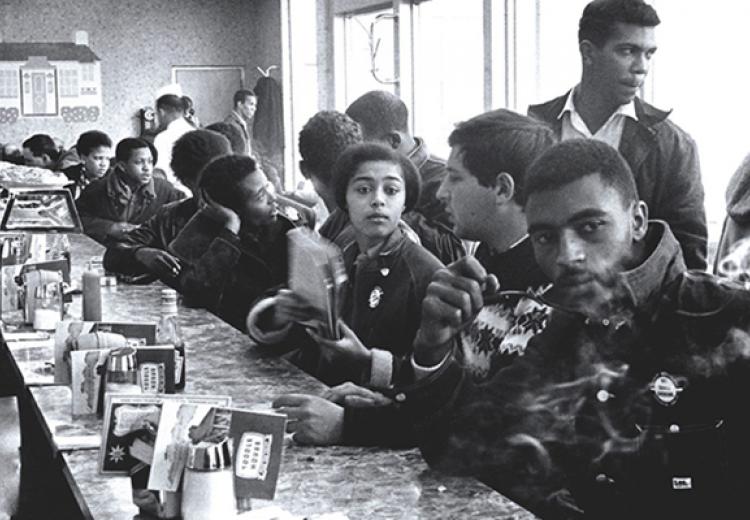

Judy Richardson (center, holding notebook) with other SNCC staff workers during a sit-in at the Toddle House restaurant, shortly before their arrest (Atlanta, December 1963). Danny Lyon photo.

“These stories explore how we overcame fear, acquired new skills, and experienced personal growth in this crucible of change. We organized in dangerous rural communities, registered voters, led mass meetings, and marched, all under the constant threat of arrests and beatings at the hands of hostile white southerners. These are accounts of strength and endurance.”

—From Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC

It is hard to imagine any movement more important for understanding the meaning of freedom and equal rights in the U.S. than the civil rights struggle in the post-World War II era. Yet, as Julian Bond succinctly argued, in most textbooks and the media, the popular understanding of that movement is reduced to: “Rosa sat down, Martin stood up, and the white kids came down and saved the day.”

The NEH 2020 Summer Teacher Institute The Civil Rights Movement: Grassroots Perspectives will provide a chance for teachers to learn a more accurate narrative from scholars and from veterans who made the history, with a focus on women, youth, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

SNCC grew out of the wave of student sit-ins that swept across the south in 1960. As the passage below points out, it was the only national civil rights group to be organized and led by young people, many of them Black southerners.

The organizing in SNCC was often based on female leaders, some of whom were prominent in their communities before SNCC ever arrived. Usually it was the local women who made it possible for [SNCC workers] to operate in these dangerous areas, offering food, shelter, and meeting places and providing protection and guidance along with a readiness to fight for freedom beside the students.

From these amazing women we SNCC staff workers gained lessons and strength that we called upon the rest of our lives. To use author Mary Helen Washington's phrase, they were "the strong black bridges we crossed over on." These are the women who nurtured and sustained their families, their churches, and us.

Unlike most other civil rights organizations in the sixties, from 1961 on SNCC focused on building organizations and introducing new concepts of leadership in the Deep South, where the harshest forms of racial segregation, economic oppression, and terrorism held sway. This meant we SNCC workers lived and worked in communities where earlier civil rights activists had been run out of town or killed.

When we made the choice to walk such dangerous paths, we helped create, sustain, and direct one of the most important social protest movements in American history. We felt the power and responsibility of being major players on history's stage. We took on the task of dismantling an ingrained system of social and political oppression that was then almost a century old, and fought to replace it with a more just and egalitarian society.

The individual stories tell one central story: that of the growth and development of a movement for freedom and equality. They show how this central objective gave purpose and meaning to all that they did, and created enduring bonds among the participants.

The summer institute’s themes are embodied in the fifty-two real-life testimonies included in this anthology. Below is a further excerpt from Hands on the Freedom Plow’s introduction that highlights those themes.

The reader of this book enters a different world, a world where danger is ever present; [where] beatings, shootings, bombings, and church burnings happen all too frequently. The issue of the day is always: how to make social and political change, how to press forward, how to keep going—in short, how to make a movement. In this world, freedom and justice are real, solid, and tangible. Freedom and justice are the reasons for being and doing and the reasons for dying.

Though the voices are different, they all tell the same story—of women bursting out of constraints, leaving school, leaving their hometowns, meeting new people, talking into the night, laughing, going to jail, being afraid, teaching in Freedom Schools, working in "the field," dancing at the Elks Hall, working the WATS line to relay horror story after horror story, telling the press, telling the story, telling the word. And making a difference in this world.

Teachers selected for the institute will receive a copy of Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC.

About the Author: Judy Richardson is co-director of the upcoming 2020 summer NEH institute “Civil Rights Movement: Grassroots Perspectives"; co-editor, Hands on the Freedom Plow: Personal Accounts by Women in SNCC; production staff and education director, Eyes on the Prize (14-hour PBS series); visiting activist scholar, SNCC Digital Gateway, Duke University; former distinguished visiting professor, Brown University.