Martin Luther: A Conversation Part I

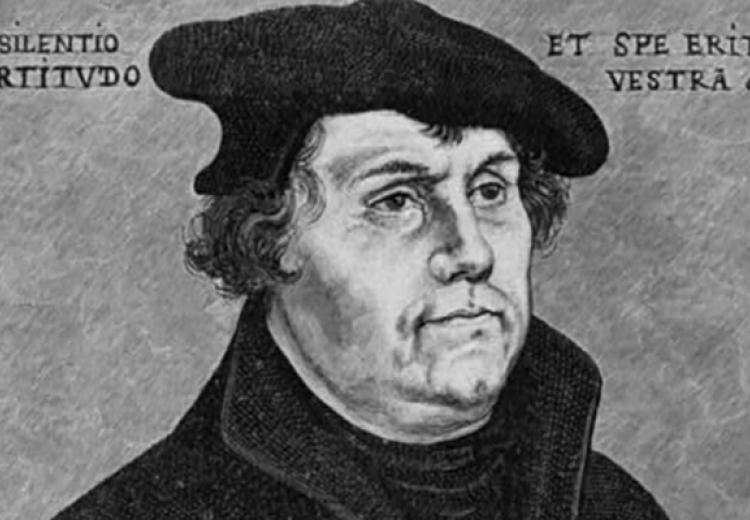

Martin Luther, engraved by Theodore Knesing

Craig Harline, professor of history at Brigham Young University, received an NEH Public Scholar grant to write about Martin Luther between the years 1517 and 1522. His book, A World Ablaze: The Rise of Martin Luther and the Birth of the Reformation, was published by Oxford University Press in October 2017. Part I of a two-part conversation between Craig Harline and EDSITEment follows.

How did you become interested in Martin Luther, and when did you decide to write a book about him?

In college, after a trip to Europe, I couldn’t think of anything more interesting I wanted to study than the Reformation, especially Luther. I ended up writing mostly about obscure people of the Reformation. Then a publisher asked me whether I’d be interested in writing about Luther for the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, and I thought, here was my chance to finally write about the most famous Reformation person of all.

There might be some confusion in the minds of many twenty-first century high school students regarding the name and the historical figure “Martin Luther.” Is Martin Luther King, Jr. a namesake?

It certainly is. Martin Luther King’s original name was Michael King, just like his father, but his father changed both his name, and his son’s, after a moving trip in 1934 to the famous Luther sites in Germany.

What aspects of your scholarship will teachers find most helpful in presenting Martin Luther, the historical figure, to their students?

I try to write all my books from the standpoint of those I’m studying. I do this because I think we learn best from the past this way—thus we see how astonishingly different it was, which is why historians say the past is a foreign country. Once we grasp that difference, we’re in a better position to translate that past to our present, and see what it has to do with us, which to me is the goal of all history: to get insight for our lives today. And which is why historians also say, like in Ecclesiastes, there’s nothing new under the sun.

What, in a nutshell, was the theological problem Luther was grappling with? Why is it still important?

He grappled with lots of them, but the one that he cared about most was How are we saved? Luther first tried saving himself, through doing as many good works as he could, as his teachers suggested, but he never felt accepted by God that way. And so he came up with justification by grace, through faith only, through simply believing in a very passive way. Thus his famous saying that good works didn’t make you a good person, but a good person (made that way by God’s grace) did good works. Those works, however, had nothing to do with your salvation; they were done after the fact, out of gratitude, and made the world a better place. And you were likely to do more of them, and to do them more freely, than when you were trying to prove yourself to God.

What did Luther think of Pope Leo X, the head of the Catholic Church in his time?

Luther always said that he never attacked Leo’s morals, or anyone else’s for that matter. Everybody was a sinner, including Luther himself, so the alleged shortcomings of Leo didn’t bother him.

What value is there, do you think, for high school students in the twenty-first century to think about the influence of some of the ancient philosophers, notably Aristotle and Augustine, on the Late Middle Ages and Early Renaissance figure of Martin Luther?

Aristotle and Augustine influenced western ways of thinking in such big ways that students are probably mostly unconscious about them. Luther was very conscious of their influence, and so maybe that’s the thing to learn: to think harder about the influences on our own ways of thinking, and how they converge or not with Luther’s view of those figures.

Why were disputations such a significant part of intellectual life in the sixteenth century?

The idea was that by arguing for and against various positions, you might come to the truth. There were practice disputations every Friday at the University of Wittenberg, where Luther taught, and public disputations whenever some big event occurred. This was the biggest public most professors could imagine, before the printing press changed all that.

Related Lessons and Websites