The Mexican Revolution: November 20th, 1910

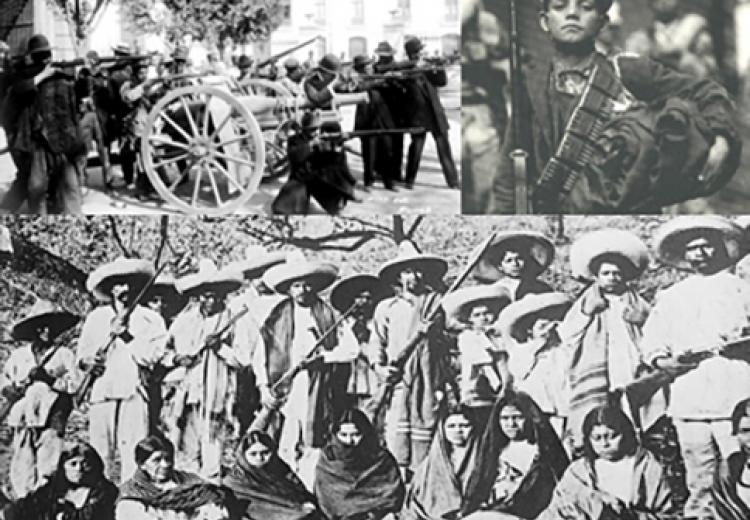

Mexican Revolution collage

"Even the land keeps a respectful silence before those men who don’t smile. … They have nothing, they are not even the owners of the dust."

—Pedro Ángel Palou, Zapata

The Mexican Revolution, which began on November 20, 1910, and continued for a decade, is recognized as the first major political, social, and cultural revolution of the 20th century. In order to better understand this decade-long civil war, we offer an overview of the main players on the competing sides, primary source materials for point of view analysis, discussion of how the arts reflected the era, and links to Chronicling America, a free digital database of historic newspapers, that covers this period in great detail.

Background

Prior to the arrival of European conquistadors, the region now known as Mexico was home to one of the world's most advanced Empires: the Aztecs. After a brutal period of colonialism and eventual conquest in 1521, the most powerful citizens were European, Spanish-born citizens or the peninsulares living in the New World. Three centuries later, in 1821, the war for Independence (starting in 1810) ended, freeing Mexico from New Spain. This was a war that, however, benefited mainly the criollo (Spanish-blooded upper class) minority. A century later, in 1910, the majority of the population of Mexico were mestizos, half-indigenous and half-Spanish-blooded Mexicans, and these indigenous peoples again rose up in a violent armed struggle, the Mexican Revolution.

The motives for waging the Mexican Revolution grew out of the belief that a few wealthy landowners could no longer continue the old ways of Spanish colonial rule; a feudal-like system called la encomienda. That system needed to be replaced by a modern one in which those who actually worked the land should extract its wealth through their labor.

Two great figures, Francisco “Pancho” Villa from the north of Mexico and Emiliano Zapata from the south, led the revolution and remain key cultural and historical symbols in this fight for social reform. The agrarista (supporter of land reform) ideals of Zapata and his followers, the Zapatistas, are summarized in their mottos: “Tierra y Libertad” (“Land and Freedom”) and “La tierra es para el que la trabaja” (“The land is for those who work it”). These slogans have not ceased to resonate in Mexican society.

The Mexican Revolution started in 1910, when liberals and intellectuals began to challenge the regime of dictator Porfirio Díaz, who had been in power since 1877, a term of 34 years called El Porfiriato, violating the principles and ideals of the Mexican Constitution of 1857.

In late 1910, Francisco I. Madero, in exile for his political activism, drafted the Plan de San Luis Potosí (Plan of San Luis Potosí), which was widely distributed and embraced by rebel movements across the nation. In this plan, Madero called for an uprising starting on November 20, 1910, to restore the Constitution of 1857 and replace dictator Díaz with a provisional government. Its main purpose was to establish a democratic republic and to abolish unlimited presidential terms. By early 1911, a large armed struggle was underway in the northern state of Chihuahua led by local merchant Pascual Orozco and Francisco “Pancho” Villa. The success of the northern troops, or La División del Norte, sparked uprisings against terratenientes across the country. (For this and other key terms see glossary).

In the southern state of Morelos, as early as 1909, Emiliano Zapata had started recruiting thousands of peasants to fight for land reform in support of El Plan de Ayala, approved by Zapata’s supporters in 1911. Under this plan land reform to help campesinos (landless peasants) by re-distributing the land back to the peasants and away from powerful landowners was paramount.

On May 25, 1911, Mexican President Porfirio Díaz resigned and left the country. Former exile, Francisco I. Madero, author of the Plan of San Luis Potosí (mentioned above) became president after the elections in 1911. He was assassinated in early 1913 by a commander of the federal forces, Victoriano Huerta, who joined the counterrevolutionaries led by Porfirio Díaz’s nephew in order to seize power. Huerta dissolved the congress after the assassination of Madero and assumed power, but faced heavy opposition. In 1914, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson sent American Marines to Vera Cruz, Mexico, to support the revolutionaries. Students can examine this intervention via the EDSITEment lesson “To Elect Good Men”: Woodrow Wilson and Latin America.” Loosing key battles to revolutionary troops, Huerta resigned in the same year and left the country.

After the end of the Huerta’s presidency, Venustiano Carranza, a wealthy landowner and chief of the Northern Coalition, gathered revolutionary and military leaders to a conference to determine the future of Mexico. Villa, Zapata, and their followers supported the Plan de Ayala for land reform (see above), in opposition to Carranza and his supporters, all of whom supported the Plan de San Luis Potosí.

Eventually, Carranza (now supported by the United States) and his followers, called for a constitutional convention to draft a supreme law of Mexico, which was later presented to congress. The final version was approved in 1917, enshrining agrarian reform and unprecedented economic rights for the Mexican people. After approval of this constitution, in 1917, Carranza as the president of Mexico proceeded to ignore its promises. As a consequence, the revolution continued until 1920. Carranza was assassinated and General Álvaro Obregón rose to power.

Art, Literature, and the Revolution

The Mexican Revolution gave birth to a variety of new artistic currents in literature, the visual arts, and music. The literature of the Mexican Revolution is a rich field and includes works recognized as masterpieces of Latin American literature such as Los de abajo (The Underdogs) by Mariano Azuela, which was published in 1915 and remains a literary classic.

Born in 1873, Azuela was a field physician with the revolutionary troops of the north. His own experiences and the circumstances that drove people to fight in the revolution, as well as the often brutal conditions of war, are depicted in his novel with sometimes crude realism. The novel narrates the story of campesino Demetrio Macías, who is considered an enemy to the local terrateniente and has to escape persecution. He leaves his family and escapes to the mountains, gathering a group of people to fight in the Mexican Revolution against the troops of General Huerta. The different kinds of people who are part of the Demetrio Macías group represent the diverse factions that fought in the revolution: the educated and idealistic men; the desperate and poor campesinos; and the different types of women who joined the struggle. Towards the end of the book, the revolutionaries appear to have lost sight of their initial goals and ideals and morale disappears.

A more recent novel, Pam Muñoz’s Esperanza Rising, tells the story of the migrants who fled to United States from a teenage girl’s point of view. The EDSITEment lesson Esperanza Rising: Learning Not to Be Afraid to Start Again (also available in a Spanish version) will be useful for teachers who want to reflect on the human costs of the Mexican Revolution.

Other forms of cultural expression dealing with the Mexican Revolution include the muralist movement in painting and corridos music. It is worth to also note that some of the most popular foods in Mexico (and outside of Mexico) come from the days of the Mexican Revolution, including famous “foods-on-the-run,” such as “burritos” or “tacos de discada norteña.”

Mexican Muralist Movement: Art for the People, Telling the People’s Story

Once the armed struggle ended, it was necessary to rebuild a shattered nation. Newly elected president, General Álvaro Obregón named José Vasconcelos secretary of public education. Vasconcelos had a serious challenge: How to succeed in educating the people of a country in which the overwhelming majority were illiterate? Public art was to be part of the answer, and a solution to start educating the nation was attempted through the Muralist Painting movement. Among the most important muralists are “Los tres grandes” (“The Three Great Ones”): Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. The Muralists viewed art not primarily as an aesthetic or expressive product but as an educative one, an art of the people.

The Muralist Movement lasted approximately half a century, from the early 1920s to the 1970s. Through it, both the art and culture of Mexico were put at the service of society and the ideals of the Mexican Revolution. Muralist painters, many of whom were no strangers to political activism, used the walls of public buildings, palaces, universities, and libraries to tell both the story of the revolution and of the daily life of the people. The mural paintings defined the nation’s identity and recognized Mexico’s indigenous ancestry. They documented the suffering of the indigenous at the hands of the Spanish conquistadores, while also recognizing Mexico’s shared history and culture. The Mexican muralists influenced artists throughout the Americas, and some murals were painted in the United States, including the Epic of American Civilization by José Clemente Orozco at Dartmouth College.

The Corridos: A Musical Legacy of the Mexican Revolution

The tradition of the corridos of the Mexican Revolution can be traced to medieval Europe’s mester de juglaría (ministry of troubadours). The corridos—the recording of events in song—are stories told in poetic form and sung to simple music, much like English ballads, that use colloquial language. The corridos grew in popularity in Mexico during the 1800s, but the Mexican Revolution, which took place in a predominantly illiterate nation with a dismantled infrastructure, gave birth to a large number of them that narrated a variety of events, such as important battles, or celebrated great leaders and fighters of the revolution.

Therefore, the corridos became a way to record, celebrate, or mourn events, places, or people during the revolution: very much like a newspaper put to music. The corrido tradition documents aspects of Mexico’s culture and identity on a wide variety of subjects. For instance, each state of Mexico has its own corrido documenting important characteristics, products, regions, and people. There are also corridos dedicated to the soldaderas, the storied, iconic female soldiers of the revolution—and even to famous horses.

In a corrido, the singer, or corridista, generally prefaces the performance by supplying the place, date, and lead character of the corrido to the audience, and then develops a story about him/her told in song. The corrido usually ends with a friendly farewell. Corridos do not hesitate to praise and romanticize great leaders as heroes, and label as “traitors” those who opposed the revolution. General Victoriano Huerta, who was president of Mexico for less than one year, is referred to in the corrido “The Taking over of Zacatecas,” as a “drunkard” with “twisted feet.”

Listen to corridos, and see the lyrics (bilingual), while singer Antonio Aguilar performs, accompanied by mariachis.

- “La toma de Zacatecas” (VIDEO) commemorates, celebrates and documents an important battle during the Mexican Revolution.

- “El centauro de oro” (VIDEO) is dedicated to Francisco “Pancho” Villa, calling him by his nickname. His soldiers were called “Los dorados” (“The Golden Ones”). This corrido celebrates Francisco Villa and his immortality in the history of Mexico.

- “Corrido del general Zapata,” (VIDEO) is a corrido to honor Emiliano Zapata, also called “El Atila del Sur” (“Atila of the South”). This corrido celebrates the great revolutionary leader of the south.

Featured Lesson Plans

- Esperanza Rising: Learning Not to Be Afraid to Start Over (includes a Spanish version)

- “To Elect Good Men”: Woodrow Wilson and Latin America