Hopi: Language of Place

The Hopi Tribe, a sovereign nation inhabiting over 1.5 million acres in northeastern Arizona, has a rich connection with the environment that pervades their culture and language. The reverence the Hopi have for corn cultivation is apparent in their art, poetry, songs, and dance celebrations.

Language of Place: Hopi Place Names, Poetry, Traditional Dance and Song, is a three-lesson ELA curriculum unit, which guides students’ exploration of Hopi language forms in order to help them to understand the Hopi’s centuries-old relationship with the land and the process of growing corn.

- Lesson 1 uncovers the Hopi homeland through maps and place names. Students examine regional place names of their own home communities and create personal maps;

- Lesson 2 involves a close study of contemporary Hopi poet, Ramson Lomatewama. Students analyze how Lomatewama’s uses figurative language to describe his intimate relationship with the land;

- Lesson 3 pursues corn as a symbol manifested in Hopi song and traditional dances. Students analyze examples of these in order to expand their cultural awareness.

Poetry

The foundation of a 21st-century American community is shared respect among individuals who come from different backgrounds, places, and experiences. Native Americans take that concept even further by valuing all the inhabitants of the earth and sky—animal, vegetable, mineral, and spirit. As first inhabitants of the United States, they model inclusiveness and diversity.

Poet Laureate Joy Harjo, a member of the Mvskoke (Creek) Nation, reminds us to pay attention to who we are and how we are connected to the world around us in her poem and the accompanying lesson for “Remember.” The companion lesson plan from EDSITEment’s and the Academy of American Poets’ Incredible Bridges project provides activities to use with students before, during, and after reading the poem.

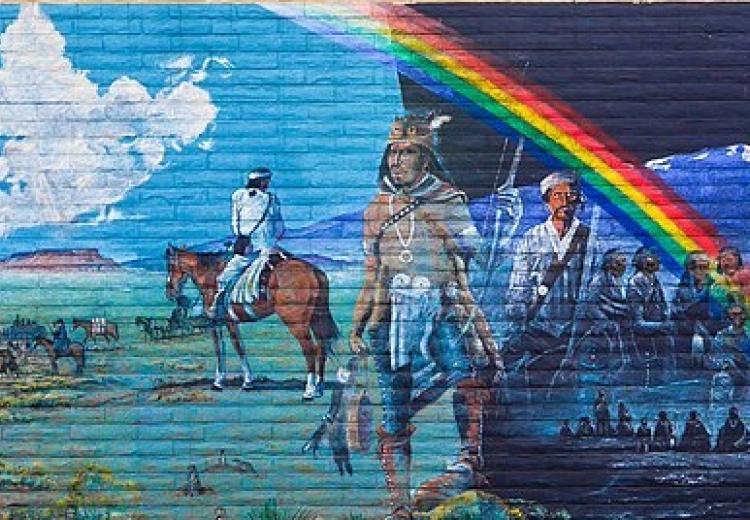

As additional teaching resources, the Chickasaw poet Linda Hogan's "Trail of Tears: Our Removal" imagines her ancestors' feelings of displacement as they were moved onto reservations in the American West. Emphasizing the onomatopoeic pleasure of the Diné word for mud (tł’ish), Naaneesht’ézhi Tábaahí (Navajo) author Orlando White's poem "Muddy" is perfect for teaching sound devices in poetry.

History & Culture

The following section is organized by grade level and includes lessons and resources for history and social studies, literature and language arts, and arts and culture classrooms.

Grades K-5

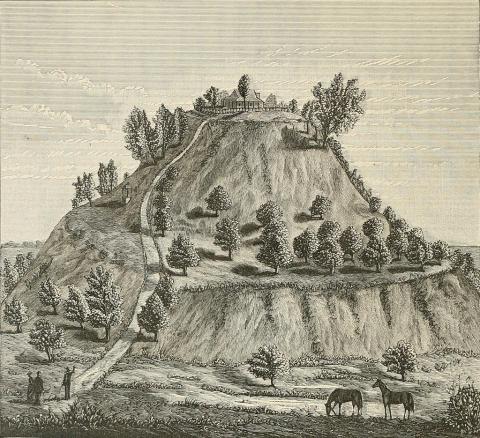

Anishinabe/Ojibwe/Chippewa: Culture of an Indian Nation: While this lesson focuses on the history and culture of the Anishinabe/Ojibwe people, you can adapt the activities to a Native American tribe that has played an historical or contemporary role in your school's region or community.

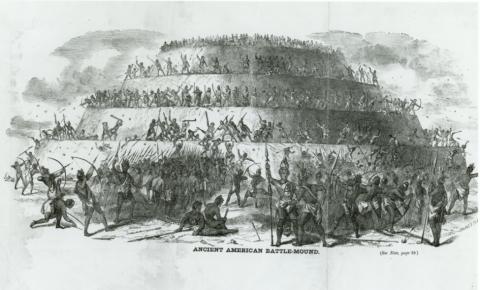

Images of the New World: In the absence of photography, Europeans brought back paintings to their home countries to share Native American customs and culture. Students will analyze similar depictions of the New World for accuracy.

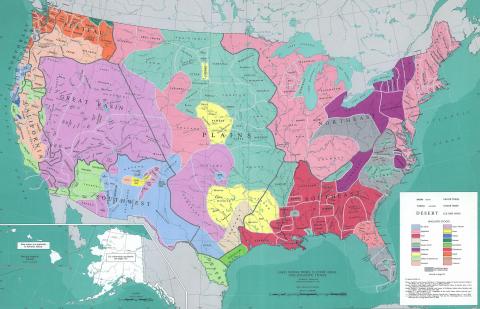

Native American Cultures across the U.S.: This lesson teaches students about the First Americans in an accurate historical context while emphasizing their continuing presence and influence within the United States.

Grades 6-8

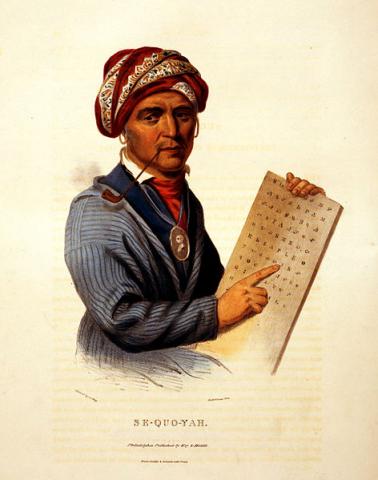

Not “Indians”, Many Tribes: Native American Diversity: In this unit, students will heighten their awareness of Native American diversity as they learn about three vastly different Native groups in a game-like activity using archival documents such as vintage photographs, traditional stories, photos of artifacts, and recipes.

Mission US: A Cheyenne Odyssey: It's 1866. You are Little Fox, a Northern Cheyenne boy. Can you help your people survive life on the plains?

Grades 9-12 and AP

Breaking Barriers: Race, Gender, and the U.S. Military: This EDSITEment and Smithsonian Learning Lab collection includes resources on teaching about the involvement of American Indians during the American Revolutionary War and questions to consider when investigating their continued involvement in the military through the 19th and 20th centuries.

Empire & Identity in the American Colonies: In this lesson students will examine the various visions of three active agents in the creation and management of Great Britain’s empire in North America – British colonial leaders and administrators, North American British colonists, and Native Americans.

Native Americans and the American Revolution: In this lesson, students will analyze maps, treaties, congressional records, firsthand accounts, and correspondence to determine the different roles assumed by Native Americans in the American Revolution and understand why the various groups formed the alliances they did.

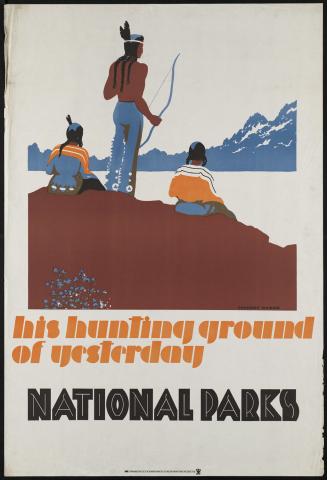

Imagined Nations: Depictions of American Indians: This Backstory podcast looks at the representations and misrepresentations of American Indians across U.S. history. Backstory is a NEH funded program.